What is Solitary Fibrous Tumor?

Solitary Fibrous Tumor Is the tumours develop from either epithelial or mesenchymal tissue. This type of tumour develops from the mesenchymal tissue which is the basic tissue of all connective tissues. These tumours aren’t named after their histological appearance, but rather are described by their macroscopic features.

These tumours may vary in malignant potential, but 80% of them are benign. They are characteristic for adults and appear very rarely in children. The causes and risk factors aren’t recognised. Malignant forms are with worse prognosis and they have a high chance for metastasing.

History

The tumours were researched since the late 19th century and were first described as haemangiopericytomas, and now they are an individual group of tumours closely related to them and to another type : a lipomatous haemangiopericytoma (tumour of fat tissue and abnormal blood vessel epithelial cells).

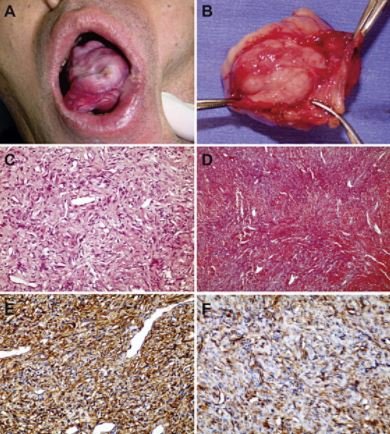

Histologically, these tumours have a collagenous stroma with a small number of cells, fibroblasts, that can show different levels of atypia. There is also a proliferation of spindle cells.

Who has risk of developing solitary fibrous tumours?

This is a rare type of tumour with incidence of 2,8 on 100 000. It is usually diagnosed in elderly, older than 50%. Men and women have equal chances for developing them. Tumours in the abdomen appear however, more equaly in women.

Where do these tumours develop?

There are three localisations of the solitary fibrous tumours:

Pleural SFT

It is a benign tumour in most cases and affects the outer sheath of the lungs, pleura. The SFTs are most commonly found in the chest cavity. It doesn’t induce any symptom or may induce mild symptoms like coughing, difficulties breathing or a non-specific pain.

Unlike other pleural tumours, there is no connection with the asbestos exposure. Another characteristic is the production of IGF2, which is a hormone much like insulin and lowers the blood sugar. This is considered as a variant of paraneoplastic syndrome.

Soft tissue SFT

They are found in the extremities. Typically, they are well marginated from the surrounding healthy tissue, but usually without a capsule. Necrosis and infiltration are displayed int he malignant forms.

Meningeal SFT

It may be found in the spinal cord and dura, and they don’t differ much from any other type of SF tumours. The tumour may or may not attach to the dura. These tumours are very rare. If they are growing along the spinal cord they may be the cause of a chronical persistent pain. Up to 23% of meningeal tumours are located int he spine. (1) (2) (3)

Symptoms

After chest cavity, these tumours are most commonly found in the abdomen and retroperitoneum, arms or thighs, head or neck. The tumour grows slowly, over the years, asymptomatically, until they reach a certain size or begin to compress viable surrounding structures.

Especially if the tumour is in abdominal or thoracic cavity, the diagnosis can be set after many years, because the symptoms develop later. When in extremities, a person may palpate a node which grows and causes symptoms of nerve compression, pain or difficulties in movement. (4)

Possible symptoms are:

- growing mass on arms or thigh

- skin is warmer on site of tumour than surrounding skin

- telangiectasia on skin, enlarged capillaries or enlarged veins

- restricted movements of the limbs, if a tumour is near a joint or affects an important muscle, for that movement,

- pleural and thoracic solitary fibrous tumour may induce coughing with or without blood, difficulties with breathing or respiratory infections, and also finger swelling

- tumours that are in the head induce symptoms such as headache, vision problems, or other symptoms of cerebral dysfunction, depending on the location,

- abdominal tumours may induce nausea, vomiting or problems with digestion and bowel discharging.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is suspected at the clinical exam, but the accurate type of tumour can be only provided with histological evaluation after a biopsy and imaging studies, MRI and CT. These tumours have specific immunohistochemical markers for diagnosis. Some of them are CD34, CD117 and EMA.

It is very difficult to distinguish malignant and benign tumours, and potentially malignant tumours. There is a need for a bioptic procedure which can be performed as an open incision biopsy or core needle biopsy. Microscopic evaluation will search for pleomorphism, necrosis and bleeding in the tumour.

However, the diagnosis of potentially malignant tumour needs to be set before the malignant alteration, while there is a process of anaplasia and dedifferentiation. Tumours less than 10 centimetres have favourable outcome than those larger than 10cm. (5) (6)

Treatment

Complete resection of a tumour via surgery with wide margins to the healthy tissue has the most success. If the tumour is with a malignant potential, there are sometimes indications for a radiotherapy and chemotherapy. There is also a possibility for embolization of the tumour, cutting the blood supply to the tumour, thus inducing necrosis in it.

Hypoglicemia as a paraneoplastic syndrome, needs to be also treated, and this is done with corticosteroids.

Prognosis

Complete resection offers 5-year survival rate of 89-100%. If the malignant characteristics of the tumour didn’t allow complete resection, there is a small chance for relapse. Long term follow-up is a must in these situations, but also in those that were completely freed from the tumour with total excision. (5)

Works Cited

- Solitary Fibrous Tumors of the Soft Tissues: Review of the Imaging and Clinical Features With Histopathologic Correlation. Wignall OJ, Moskovic EC, Thway K, Thomas JM. 2010., American Journal of Roentgenology. 195(1), old.: 55-62.

- A., Gullett. Soft tissue.Fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumors.Solitary fibrous tumor (extrapleural). [Online] [Hivatkozva: 2017. 03 16.] http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/softtissuesft.html.

- Meningeal solitary fibrous tumor: report of a case and literature review. Deniz K, Kontas O, Tucer B, Kurtsoy A. 2005., Folia Neuropathol. 43(3), old.: 178-85.

- Vy., Ng. Solitary Fibrous Tumor. emedicine Medscape. [Online] 2015. [Hivatkozva: 16. 3 2017.] http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1255879-overview.

- MT., Niknejad. Solitary fibrous tumour. Radiopaedia. [Online] [Hivatkozva: 2017. 3 15.] https://radiopaedia.org/articles/solitary-fibrous-tumour.

- Solitary fibrous tumor: A pathological enigma and clinical dilemma. G., Langman. 2011., Journal of Thoracic Disease. 3(2), old.: 86-7.